Because it could meet the portability and communications requirements of socially engaged artists with messages to convey, the Portapak became THE reference in cameras. It offered great freedom to filmmakers, communities and camera operators who wished to share their stories and opinions with a wide audience.

Refer to the “Additional resources” section to see a glossary of technical terms.

A video camera in the service of the community

As its name suggests, the Portapak was designed to be portable and easy for solo filmmakers to operate alone. Its name could hardly be more appropriate, could it?

The Portapak Sony Video Rover II (AVC-3400) was launched in 1970. The result of advances in 1960s VCR technology, this lightweight, easy-to-handle device was made up of two components: a camera and a portable recorder. The camera was equipped with a microphone that transmitted audiovisual signals to the portable recorder, which was linked to the camera by a cable. The portable recorder used videotape, which could be rewound and viewed right after a scene was recorded. This was not possible with film cameras. The Portapak produced a low-definition black and white image that could be viewed on televisions.

This new camera was frequently used by community video production workshops, such Vidéographe in Montréal, and feminist video collectives, such as Vidéo Femmes in Quebec City, to create socially engaged works.

Examples of videos

Philosophie de boudoir, directed by Helen Doyle and Nicole Giguère, 1975

Cinémathèque québécoise collection. Helen Doyle and Nicole Giguère (CC BY-SA-ND).

Satire of the Women’s Show in Quebec City in April 1975. To believe in it, must one be naive, utopian or simply of a philosophical nature? (Cinémathèque québécoise program)

Philosophie de boudoir, directed by Helen Doyle and Nicole Giguère during the Women's Show

At the Women’s Show in Quebec City during International Women’s Year, directors Nicole Giguère and Helen Doyle produced a vox pop by interviewing women and men on so-called female themes. The misogynistic comments recorded live were later combined with humour during the editing process. Through these interviews, the filmmakers revealed the sexism entrenched in the very structure of the show, as well as in people’s mindsets.

This clip clearly shows how easy it was for them to record footage as they moved through the show with the Portapak. The camera allowed them to easily film attendees and record their words. The images generated by the Portapak were of relatively poor quality and degraded over time. However, the filmmakers were able to circulate and converse freely.

Philosophie de boudoir, directed by Helen Doyle and Nicole Giguère, 1975

Cinémathèque québécoise collection. Helen Doyle and Nicole Giguère (CC BY-SA-ND).

Satire of the Women’s Show in Quebec City in April 1975. To believe in it, must one be naive, utopian or simply of a philosophical nature? (Cinémathèque québécoise program)

Note: The information in square brackets describes the audio and visual content of the video. The remainder of the text corresponds to dialogue. The French passages in the video have been freely translated and are written in italics.

[1:06 minute sequence.]

[Indoors. The Women’s Show, Quebec. Black and white. Narrow horizontal glitch lines briefly appear throughout the clip

[Medium close-up of two women, standing, at the show. It is a chest shot of the directors. In the background is a book display.]

[The woman on the right, Helen, takes a microphone from Nicole, who is on the left. She speaks while looking around her and then back at Nicole.]

Nicole, I heard that this year, because it’s International Women’s Year, there are several information booths, so it would be fun to go and visit them as well.

[Helen gives the microphone back to Nicole, who begins to speak, first while facing the camera, and then while turning her head to look around her.]

Yes, they don’t sell products, but they do try to sell ideas. We’ll try to find out what kinds of ideas they’re selling. What’s their view of the Women’s Show? What do they think of women’s liberation? What are they doing for it? We’ll ask all these types of questions at random to the people we encounter while walking around. So, we invite you to follow us through the Women’s Show.

[Noise of a crowd] [The woman on the right takes back the microphone and the two women head towards the left. In a single movement, the camera pans out to follow their movement and then zooms back in on the two women. Viewed from behind, they walk through the crowd. Passers-by walk in front of the camera and the two protagonists disappear from view.]

[The shot is divided in two: On the left is a couple and on the right are the two directors. All are in profile. The man occupies most of the frame. Nicole is also in the frame, but Helen can hardly be seen. They both hold the microphone. Behind the man is a woman, in the background, hidden by the man’s body. Nicole speaks to the man.]

Nicole: What do you think of women’s liberation?

[Slow zoom toward the man, who is looking at his interviewers, who are on the right-hand side of the frame. The microphone is still visible in the frame, but the directors are now out of the frame for the duration of the exchange.]

Man: Well, they’ve helped us so much, we can help them a bit to be liberated…

Nicole: Yes. So, what does it mean to be liberated?

Man: Well, there are a lot of things in liberation, eh? Like us, we know that we’ve enjoyed a lot of liberation.

[The woman, behind the man, faces the camera and smiles. Helen, still off-screen, begins to speak. The camera makes a small jerky movement toward the left to readjust the frame.]

Helen: What, in particular, have women done to help you?

[The woman, who was facing the man, now turns to face the directors. Her face is now entirely hidden by that of the man. The camera makes small jerky movements upward and to the left and to the right to adjust the frame. The woman’s face becomes visible again.]

Man: Well, it’s a bit too much to list…

Helen: Yes, that’s true! [Laughter]

Man: For me, anyway… [Laughter]

[The image stabilizes.]

Nicole: So, do men still need to be liberated too, or are they completely liberated?

[The woman looks at the man, then at the camera and at the floor, and then returns to profile, hidden behind the man once again.]

Man: No, there are still a few little things. Especially from the point of view of… Small things, yeah, and I can’t list them in front of women, it’ll make them jealous.

[Laughter]

[The woman turns her back. A passerby walks in front of the camera. He is blurred. The woman exits the frame.]

[End of scene.]

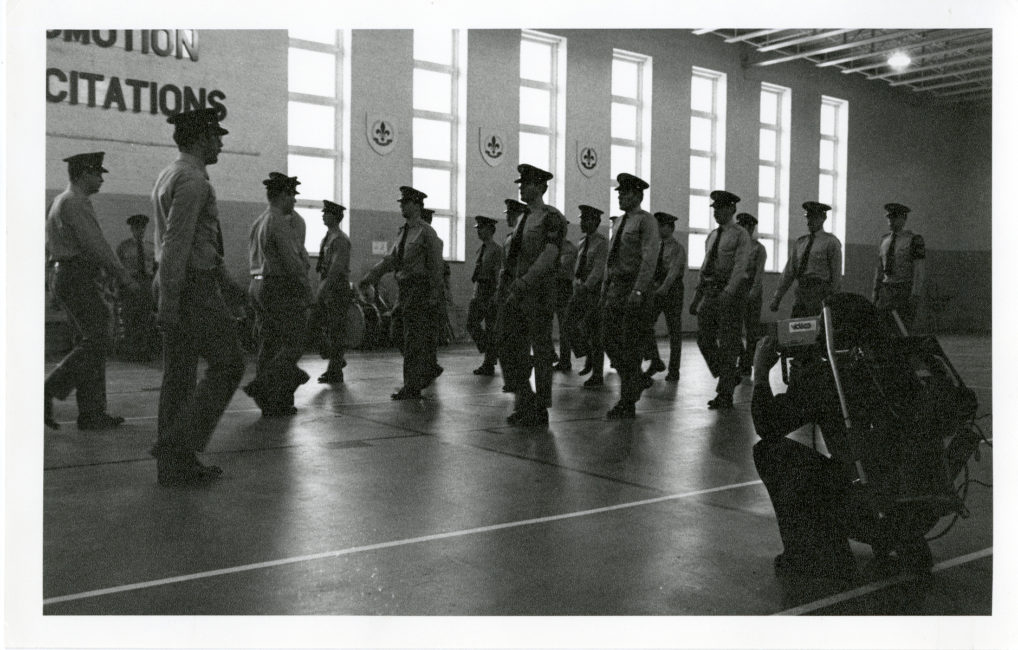

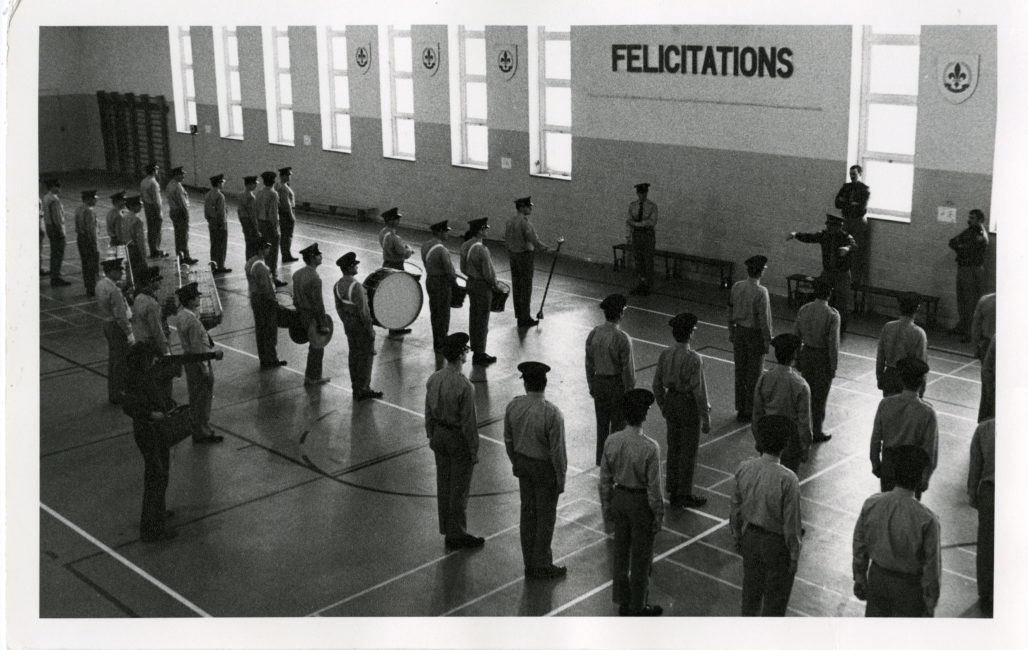

Le Magra directed by Pierre Falardeau and Julien Poulin in 1975

© Films Pea Soup inc.

The training of future police officers at the Nicolet Police Institute is shown in its various stages, as it promotes conformist attitudes and conditioned behaviours. With various camera perspectives, the film emphasizes the moral and physical rigidity of this indoctrination process, which embodies both alienation and loss of individuality (Cinémathèque québécoise program).

Le Magra

From the very beginning of the clip, the viewer gets a feel for the Portapak’s small size and usefulness in almost any location, such as inside a car. One of the two directors carries the camera and the recorder, while the other is responsible for the boom microphone. They are linked by cables, so they must remain close to each other.

For this film, the directors used a video camera, which allowed them to shoot freely in tight spaces. Through their choice of shots, which were only possible because the camera was so easy to carry and could be operated by two people, they created a critical discourse.

Le Magra directed by Pierre Falardeau and Julien Poulin in 1975

© Films Pea Soup inc.

The training of future police officers at the Nicolet Police Institute is shown in its various stages, as it promotes conformist attitudes and conditioned behaviours. With various camera perspectives, the film emphasizes the moral and physical rigidity of this indoctrination process, which embodies both alienation and loss of individuality (Cinémathèque québécoise program).

Note: The information in square brackets describes the audio and visual content of the video. The remainder of the text corresponds to dialogue. The French passages in the video have been freely translated and are written in italics.

[1:06 minute sequence.]

[Inside a moving police car. Daytime. Black and white.]

[The viewer has the same view from inside the police car as the operator of the Portapak camera, who is sitting on the back seat. On the front seats are two uniformed police officers. One is driving and the other, on the right, is listening to a radio message from the station. Two rearview mirrors on the front windshield reflect the police officers’ hats. The snow-covered road is visible outside the vehicle’s windshield. The camera jumps slightly with each bump in the road, mirroring the car’s movements.]

[Off-camera voice from the radio.] Could you come to the QPI to pick up two individuals named Pierre Falardeau and Julien Poulin, who are currently producing a video report on the school and who are wanted by the Montreal police under warrant number 197-260? I repeat, warrant number 197-260.

Description of Mr. Falardeau: About 5 foot 11, light brown hair, wears a beard. And his partner, Mr. Poulin: He wears a moustache and has black hair, which is quite long.

[The police officer on the right, in the passenger seat, replies to dispatch.]

10-4, we’re on our way.

[He speaks to the driver of the car.]

Turn on the siren. When we arrive, we’ll block the main entrance and go in through the main door. We’ll grab them there.

[The driver turns on the siren.] [Sound of a police car siren.]

[Inside the Quebec Police Institute. Black and white.]

[The sound of footsteps hitting the ground in unison.] [Police officers marching three by three. In the background, the reflections of two men can be seen in a mirror. They are Falardeau, standing, holding a Portapak camera in his two hands, with his eye on the viewfinder, and Poulin, crouched down, boom pole in hand and wearing headphones. On his back, Falardeau is carrying a bag containing the Portapak sound recorder, which is connected to the camera by a cable. Poulin points the boom pole toward the ground. An off-camera officer is shouting the pace.] Left! Left! Left, right, left!

[End of scene.]

Photograph from the filming of Le Magra, 1975. Cinémathèque québécoise 1995.1754. PH

Photograph from the filming of Le Magra, 1975. Cinémathèque québécoise 1995.1754. PH

Origins of a video camera

To better understand the Portapak and the idea behind its creation, it must be looked at from a post-war point of view. The creation of video cameras in the 1950s was influenced by several factors, including ideas about communication and a need for compatibility with the burgeoning medium of television.

SONY was created in 1946. A team of about twenty engineers focused on developing and producing communications equipment. They quickly met with success in Japan, and international success soon followed.

Photograph of Nobutoshi Kihara, engineer at SONY. ETHW.

https://ethw.org/Oral-History:Nobutoshi_Kihara

The Portapak was one of the first portable video systems to be made available to individuals, amateurs, artists and independent producers in the 1970s.

The creation of the video camera was influenced by the principle of feedback—a major innovation born of video technology and later popularized by video art.

In 1965, SONY launched the Portapak, which was sold with a tripod and a microphone. It was the first in a long series!

Video became a tool for the people, notably through the creation of community media, radio and television. It hit the market in the era of women’s liberation and the social movements of the 1960s and 70s. It was born of a desire to break free from the codes and structures of traditional cinema and get closer to “real people.” This new ability to leave the studios behind, record subjects’ stories and share them on alternative community networks became a tool for participating in the social debates of the day. The cameras could record and broadcast political events and actions. Video very quickly became an instrument of subversion and protest for those on the fringes of society.

Portapak AV-3400 and AVC-3400 technical data sheet

Specifications

- Measurements (camera only)

- 38 cm x 7 cm x 13 cm

- Measurements (recorder)

- 27,7 cm x 7,1 cm x 26,6 cm

- Weight (camera and recorder)

- 11 kg

- Materials

- Plastique, métal

Components and accessories

- Cable

- The camera and microphone send signals to the recorder via the cable.

- Portable recorder

- The recorder receives signals from the camera and the microphone, as well as the signal to rewind so the recorded footage can be viewed. This is not possible with a film camera..

- 1/2-inch black and white magnetic tape

- Unlike film, magnetic tape can be erased and reused several times. It can record about thirty minutes of low-definition images.

- 7-56 mm lens

- The zoom lens allows the camera operator to quickly adjust the frame during the shoot.

- Electronic viewfinder

- The electronic viewfinder makes it possible to see exactly what is being filmed. It can also be used to view the recorded video.

- Batteries with a run time of 45 minutes

- The recorder can be powered by batteries, giving the operator greater freedom during the shoot. It can also be plugged into an electrical outlet or a car.

- Integrated mono microphone

- The camera is equipped with an integrated microphone, making it very silent. The sound quality can be adjusted during the shoot through the use of headphones. An external microphone can also be connected to the device.

- Tripod

- The tripod is often used when filming interviews. To mount the camera onto the tripod, the camera’s handle must be removed.

- Shoulder bag or backpack for the recorder

- The bag frees up operators’ hands during shoots, allowing them to focus their attention on the camera. The camera and the recorder can be operated by the same person.

Features

- Portability

- The Portapak is an alternative to the very heavy professional television cameras used in studios. It can be operated by a single person working on location. However, it weighs 11 kg.

- Automatic functions

- The camera features automatic functions that simplify its operation, rendering it accessible to amateur users.

Operation and handling

The Portapak made it easier than ever for solo filmmakers to film on-location television reports. Its portability and automatic functions made it relatively easy to use.

The basic steps for operating the camera consisted in connecting it to the recorder, pressing the shutter button, letting the camera warm up and adjusting the settings, just like with film cameras. The battery, headphones and preloaded recorder could be transported in the satchel.

In practice, however, several steps had to be completed before shooting could begin. It wasn’t completely instantaneous!

Anon. n.d. SONY Videocorder AV-3400 Owner’s Instruction Manual. From the collections of Richard Diehl. 9 pages.

pdf (8.78 MB)SONY AV-3400 Owner’s Instruction Manual

This nine-page manual provides step-by-step explanations of the camera’s operation and various settings. It also proposes good shooting habits. It contains illustrations to accompany the descriptions. The manual is organized into the following sections: Precautions, Location of Parts and Controls, Power Source, Tape Threading, Recording with the Video Camera, Recording TV Programs, Tape Playback, Sound Dubbing, Tape Erasing, Battery Charging, Maintenance, Splicing Tape and Specifications

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Anon. n.d. SONY Videocorder AV-3400 Owner’s Instruction Manual. From the collections of Richard Diehl. 9 pages.

pdf (8.78 MB)Selected excerpts:

The SONY AV-3400 is a portable record/playback Videocorder designed to operate with the SONY AVC-3400 Video Camera. The system will record live action, and the recorded picture can be immediately played back and viewed on the camera viewfinder screen. It will greatly aid in teaching, training, promotional activities and in hundreds of other applications. Please read this manual carefully and keep this booklet handy for future reference (p. 2).

Precautions: Keep the Videocorder away from extreme temperatures and excessive dust and moisture. Keep both Videocorder and video tapes away from strong magnetic fields and sources of electronic noise such as motors, generators, and voltage regulators. Avoid subjecting the tape transport mechanism to unnecessary shock or impact. Do not place anything or press down upon the head drum cover. The rotary video heads are precisely engineered. Do not touch the heads except during cleaning or tape threading (with motor off). Never touch the heads while the head drum motor is running (p. 3).

Goldberg, Michael. 1974. The Accessible Portapak Manual 1974-1984. Cinémathèque québécoise collection. 2017.0001.01.0054.FD

pdf (2.68 MB)Portapak user manual for film crews.

These excerpts from the manual provide a very detailed explanation of how to operate the camera. The original version contained 70 pages. The writing is relatively small and certain sections are accompanied by sketches.

The manual outlines some of the problems that could be encountered during shoots. It was not intended for first-time users. It also takes into account the collaboration and cooperation between filmmakers and the shared ideology that underlies their work.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Goldberg, Michael. 1974. The Accessible Portapak Manual 1974-1984. Cinémathèque québécoise collection. 2017.0001.01.0054.FD

pdf (2.68 MB)Transcript of pages one and two:

Dear friends,

Here’s a photocopy of the manuscript for our ‘Accessible Portapak Manual.’ We hope to distribute the final version free, on 3-ring binder paper.

This is the text only – the manual will contain drawings, photographs and a less compact layout. Please, as you go through it, make notes on things that need correction or should be cut out, anything that is not clear, as well as constructive criticism from your general impression.

Here are some comments already received :

- “By using different writing styles, make a clear separation between beginners’ information and more complex sections for people already into it.”

- “When tracing troubles, one person should check everything out. If a bunch of people are trying to figure out what’s wrong, it just gets more confusing.”

- “Separate your personal opinion from facts + technical info.”

- “Re. page 7A (4 lines above reference #6). By pulling on the wires it is more likely that the wiring will go open-circuit.”

If you are willing, add any information you think would be useful, and do help with definitions.

I feel this manual is already the result of our collective experience. Please help get it to the space of turning other people on to using the Portapak well.

Love, Michael Goldberg

Video Exchange Satellite

261 Powell Street, Vancouver, B.C. Canada V6A 1G3

Introduction: Because of its relative low price, small-format video has spread quickly around the industrialized world. Versatile and easy to learn, the Portapak has nurtured the concept of access, of sharing this resource by many people with varied viewpoints and interests. This radically changes the television process, taking communications media out of the hands of professionals and creating a new mirror of society.

Communication is a right which must be earned in a world where people can choose not only what they read but also what they watch and listen to. The message must spring from felt values; it must also be communicated well. If we choose to make use of this medium, we should learn its techniques, its possibilities and limitations, and treat it with care to gain the best of use of it.

I hope this manual will help foster the growth of a new communication environment from the base up. It centres around SONY AV3400, because it is widely available and frankly what I have used most; however, I would not recommend this Portapak over those of any other manufacturers. This is not an instruction book for someone using the Portapak for the first time; it should rather serve to supplement an introductory workshop given in person. I’ve included much information for regular users as well, the result of the collective experience of many friends. Michael Goldberg.

Table of Contents: Playback; Threading, head-cleaning; Recording; Vision; Sound; Batteries; Tape; Electronic and optical transfers; Feedback, delays; Mobility; Europe; Extreme environments; Tips, tape cataloguing; Workshop, reminder sheet; Maintenance; Dos and don’ts; Trouble shooting, Glossary of terms and an Index.

Copyright 1974 – M. Goldberg. This manual or any portion of it may not be sold or published, free circulation only.

This portion of work on the manual has been completed with the financial assistance of: the Educational Research Institute of B.C., the Provincial Educational Media Centre, with thanks to the encouragement of many friends and Donna’s patience (it’s not over yet!).

The videographer was relatively free to move around and had the option of using the viewfinder to frame the shot, although this was not necessary. Unlike film cameras, in which the recorded images could be ruined if light entered the viewfinder, this device provided much more mobility. In this sense, it was much less restrictive.

Videographers could operate the camera and recorder on their own, but together these two pieces of equipment weighed almost four times more than the Bolex! It was therefore common to see teams of two operate this device: One person held the camera while the other handled the recorder and/or the microphone.

Video allowed more projects to be completed because shoots took less time and required smaller crews with less rigid hierarchies. These cameras ultimately provided videographers with great freedom and independence.

With video, I’m in constant direct contact with the image, which is not the case with film. In fact, given the daily cost of a shoot, I have to put the image in the hands of specialists (director of photography, camera operator, focus puller, colour timer) who will use their expertise to get the best possible results (hence the “glossy-looking” lighting and sets of “standard” films). With video, it’s okay if I make mistakes (and what’s more, I can control the image on the spot, find solutions, start over and experiment). So, I get to handle the camera, frame the shots and control the lighting however I want. Video is my image studio, the place where I can do my research and stretch the limits of my creative freedom [Translation]

(Danielle Jaeggi in Minne 2016, 20)

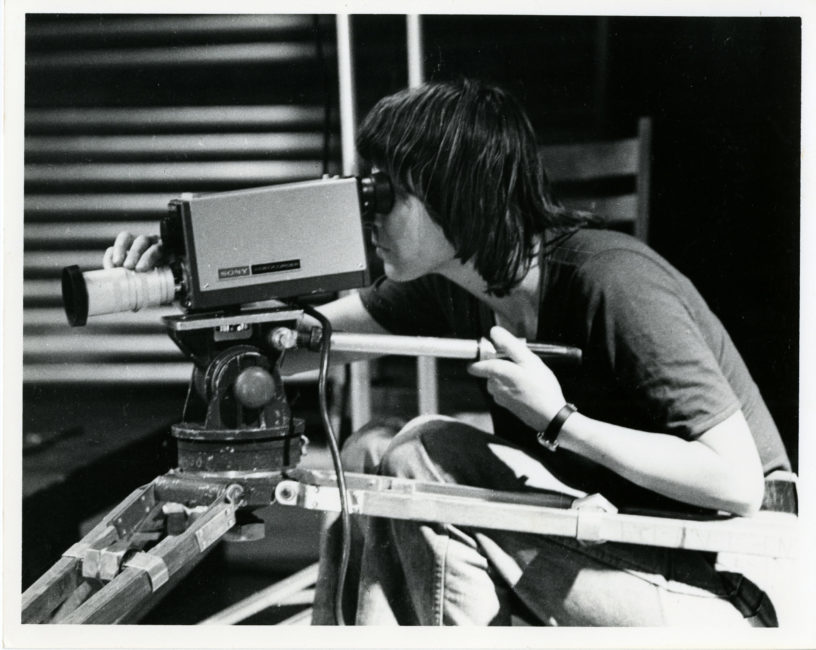

Photograph of Nicole Giguère in Paris, 1977. Personal collection of Nicole Giguère.

© Nicole Giguère

Photograph of Hélène Bourgault on the set of Chaperons rouges. The Portapak has been mounted on a large tripod (not the original one designed by SONY). Cinémathèque Québécoise collection: Fonds Helen Doyle. 1995.0736.PH.

© Helen Doyle

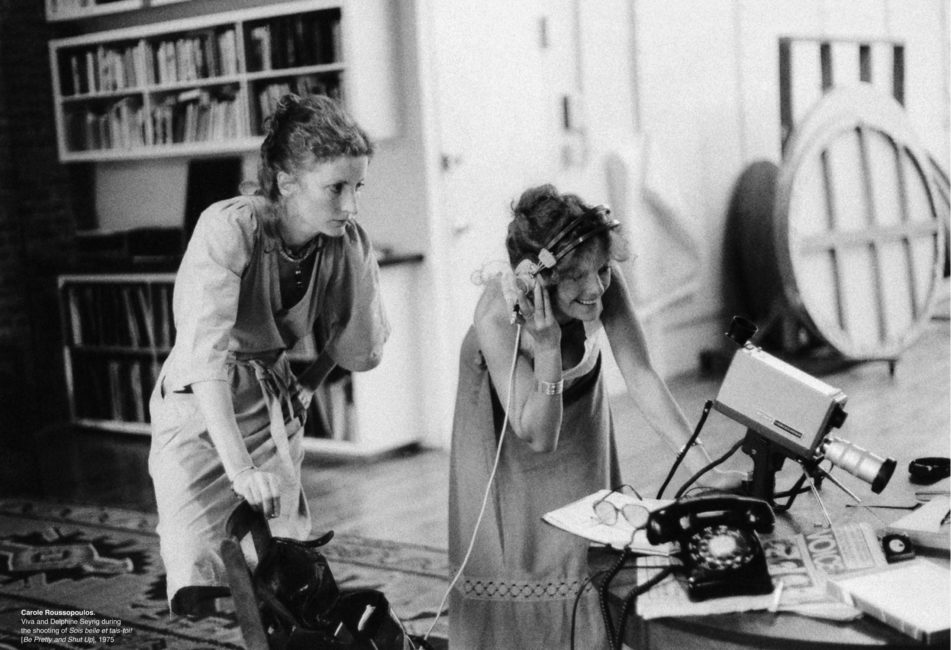

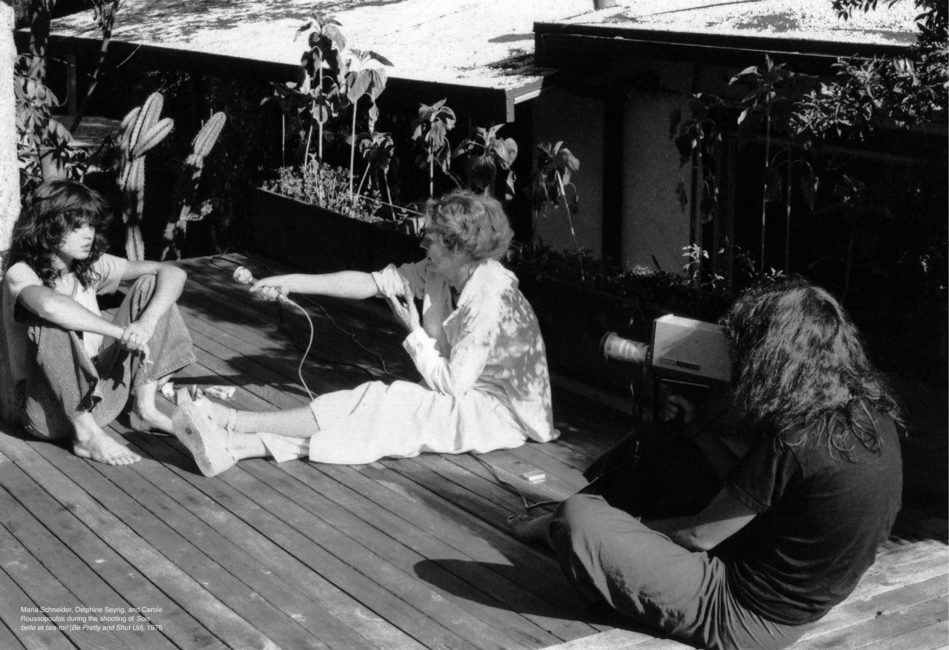

Photograph from the set of Sois belle et tais-toi, 1975. On the right, Delphine Seyrig watches and listens to a recording directly through the camera’s raised viewfinder. Photo from the book Defiant Muses: Delphine Seyrig and the Feminist Video Collectives in France in the 1970s and 1980s, p. 32-33.

Photograph from the set of Sois belle et tais-toi, 1975. On the right, Delphine Seyrig watches and listens to a recording directly through the camera’s raised viewfinder. Photo from the book Defiant Muses: Delphine Seyrig and the Feminist Video Collectives in France in the 1970s and 1980s, p. 22-23.

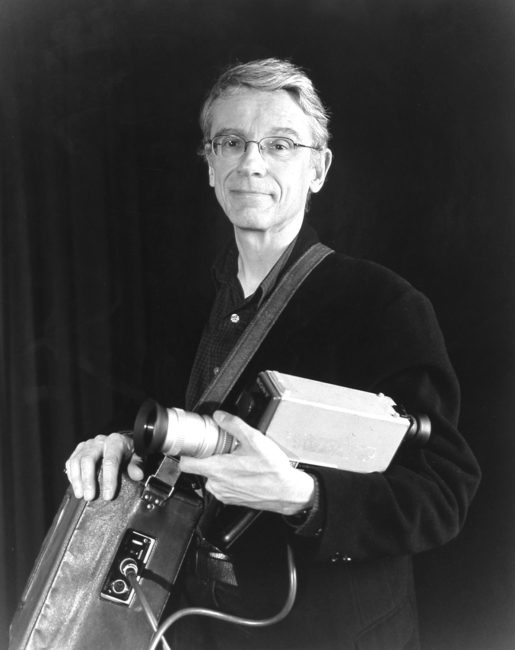

Photograph of Bernard Émond with a Portapak. Cinémathèque québécoise collection 2004.0059.PH.

©Gabor Szilasi

Who used the Portapak?

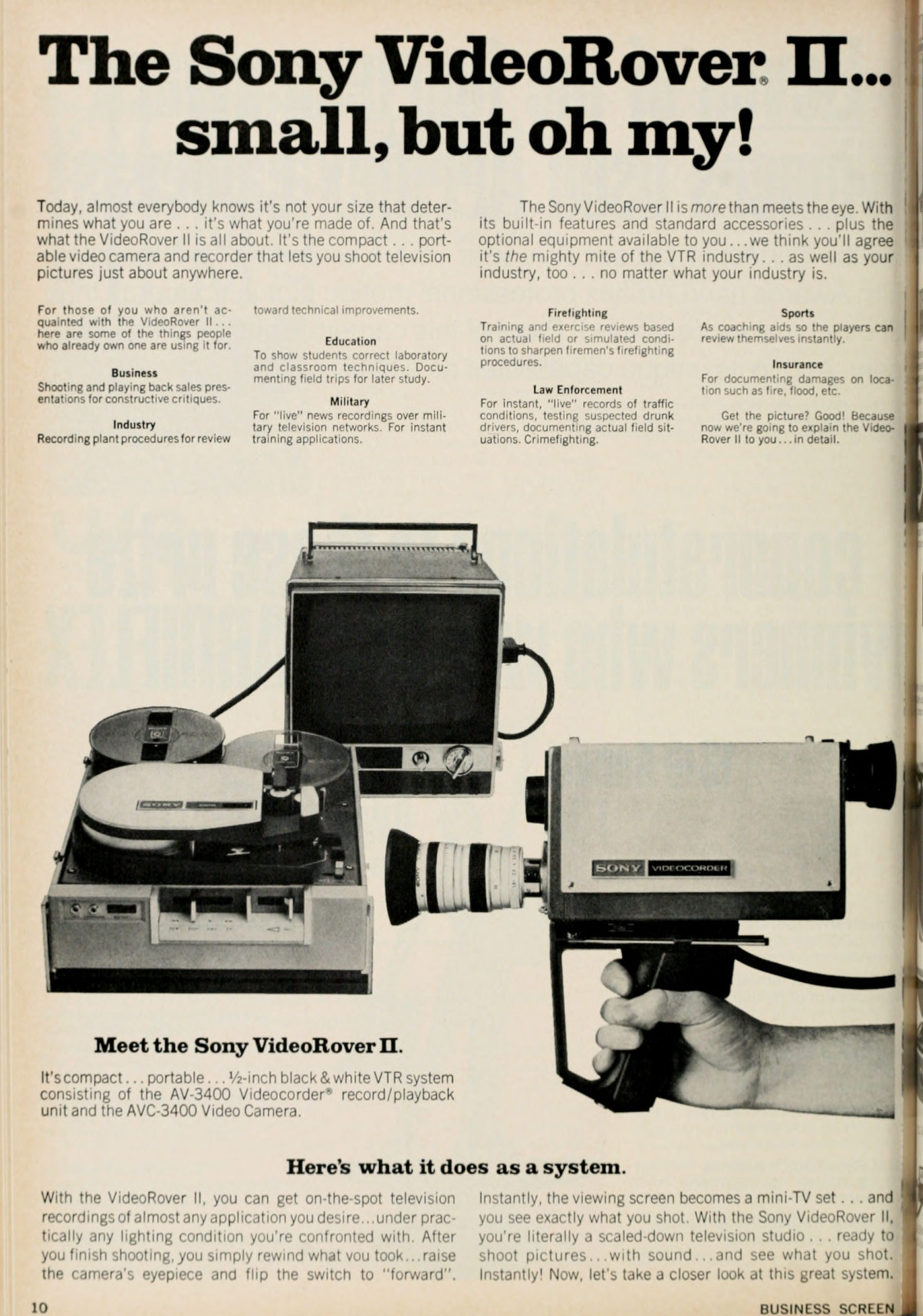

Advertisement from Business Screen Magazine, 1971, p. 430.

Public domain

The Sony VideoRover II... small, but oh my!

Advertisement for the SONY VideoRover II. The first paragraph reads, “Today, almost everybody knows it’s not your size that determines what you are … it’s what you’re made of. And that’s what the VideoRover II is all about. It’s the compact … portable video camera and recorder that lets you shoot television pictures just about anywhere.”

According to the brochure, this camera could be used in many fields, including not only business, industry, education and sports, but also the military, firefighting, law enforcement and insurance!

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Advertisement from Business Screen Magazine, 1971, p. 430.

Public domain

Users of this camera included private individuals, amateur filmmakers, community activists (feminists, racialized persons, First Nations, LGBTQ+) and visual artists of all types. Professional filmmakers and journalists, as well as cooperatives and schools, also used it. Despite the equipment’s relatively high cost (approx. $1,500 US in 1970, equivalent to $14,000 Canadian dollars today), it was a commercial success, and thousands of units were sold throughout the world.

This equipment could be borrowed from co-ops, making it a great tool for producing works of community engagement. An example of this type of co-op in Montréal is Vidéographe, the distributor of Le Magra. As well as offering rentals, it is a space for creating and distributing socially engaged works.

In Quebec and in France, video was widely used by women in an effort to raise issues about gender equality. These videographers wished to make a change and push society to evolve by revealing its flaws. For example, Vidéo Femmes, a collective founded by Helen Doyle and Nicole Giguère, was dedicated to producing and distributing videos made for women by women.

The videos I produced at Vidéo Femmes allowed me to shoot, experiment, learn and pursue my life with great happiness over the past few years. Working with female crews in a respectful and trust-based environment, that’s what video gave me. [Translation]

Lise Bonenfant in Copie Zéro, 1985, n. 26 (online, French only).

The Portapak also served the community by making it possible to broadcast content to larger audiences via television. It was used to create content for Télévisions Communautaires Autonomes (TCA)—a federation of approximately 40 community television stations incorporated as non-profit organizations working in local/regional production—that was broadcast on their local community channels. These TCAs adhere to and promote their guiding values and principles. They are also citizen-led.1

In Quebec, citizen groups chose to implement this type of community media because they believed in its ability to rally the community around important issues. Speaking up was seen as a way to contribute to social change. Television became an accessible and instructive tool for activists who wished to get involved in their communities.

Similarly, artists from many other fields adopted video as a new mode of expression that served as an extension of cinema. It was a growing medium that opened the door to new ways of experimenting.

In addition to being a socially engaged mode of communication, video therefore also became an experimental art form.

Additional resources

This motion picture glossary will help you better understand some of the terminology used.

Are you the inquisitive type? Would you like to learn more about Portapak and the filmmakers who used it? The following websites will provide you with additional information.

- Opération boule de neige, directed by Bonnie Sherr Klein in 1969, demonstrates how the residents of a Montréal neighbourhood took collective action and how video helped them to do so. (French only)

- Trailer for Insoumuses, directed by Callisto McNulty in 2018, featuring images of the Portapak being used by Carole Roussopoulos and Delphine Seyrig. (French with English subtitles)

- Here Come the Videofreex, directed by Jon Nealon and Jenny Raskin in 2015

- Wikimedia conference organized by the Cinémathèque québécoise: “Vidéo Femmes : une histoire.” (French only)

- Explanation of video art in Canada.

- Copie Zéro no.6, April 1980 devoted a page to Vidéo Femmes. (French only).

- Bensinger, Charles. 1981. The Video Guide. Santa Barbara: Video-Info Publications. Online book.

Bibliography

Anon. n.d. 1974. SONY Videocorder AV-3400 Owner’s Instruction Manual. From the collections of Richard Diehl. 9 pages.

Bourdeau, Roger. 2015. Helen Doyle cinéaste : la liberté de voir. Montréal: Vidéo femmes. Les Éditions du remue-ménage.

Goldberg, Michael. 1974. The Accessible Portapak Manual 1974-1984. Cinémathèque québécoise. 18 pages.

Minne, Julia. 2016. “Collecter, conserver et valoriser la vidéo légère en France (1968-1981) et au Québec (1967-1989).” Master’s dissertation. Paris : Université Paris 8.

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. 2019. Defiant Muses: Delphine Seyrig and the Feminist Video Collectives in France in the 1970s and 1980s. Exhibition catalogue 2019-2020. Internet archive.

Want to find out more?

Take an audio journey into the world of this device.